With the recent death of the great actor and director Robert Redford, I have embarked on a kind of Robert Redford retrospective. I am watching three films that I have heard are some of his greatest: Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, Three Days of the Condor, and All the President’s Men. Next on deck for me is his directorial debut, Ordinary People. That one cleaned up at the Oscars in 1980. Not bad for a first-time effort, I would say.

But what I really want to discuss here is the cinematography of the films of the 1970s, during peak New Hollywood.

My Beef with Modern Cinematography

It seems like movies today have a washed out, dull tone to them. To my eye, they almost look grey. The problem, from what I have read, is twofold. Firstly, cinematographers have become enamored with high dynamic range (HDR). This allows for a wider range of brightness and eliminates (mostly) the blown out light area and clipped dark areas on the frame. As a result, things that should be in the shadows are now seen, and objects in brightly lit areas are more apparent, taking attention away from the subject of the frame.

The second problem is that cinematographers do not want to make artistic choices on the set. The attitude seems to be, “We’ll fix it in post.” Sometimes that works, other times it does not. As a still photographer, there are some things you just cannot fix in Lightroom or Photoshop (e.g., bokeh, lens flare). If you shoot RAW, then there is much you can fix. But if you shoot JPEG, you must decide things like white balance and exposure when shooting, not in post-production. From what I understand, the format used in digital filmmaking is ProRes RAW, which should allow cinematographers a wide latitude when it comes to setting color, brightness, and contrast in post. Yet we still get dull, washed-out scenes.

Ultimately, it seems there is a certain artistic conservatism that restrains them from having a unique and bold vision for a film.

Could costs be a factor as well? Possibly. If the production is shot in ProRes RAW, the temptation certainly would be to get it recorded then fix everything in the editing room. That is certainly a lot cheaper than having to reshoot scenes with actors, sound engineers, lighting engineers, etc.

Netflix productions seem to be the worst when it comes to cinematography and lighting. My wife likes to watch a barbecue contest they produce called Barbecue Showdown. The show’s lighting is dark, and the colors are dull, giving it a creepy feel.

Same was true for a baking reality show they aired. The theme for the show was a state fair. Again, it was dark and washed out with very poor lighting. If you have ever seen the 1983 film Something Wicked This Way Comes, this baking show evoked the look of that film. I was just waiting for Mr. Dark or Pennywise to pop out from behind a tent.

You cannot blame Netflix, though. Look at the amount of new content they produce every year. With their release schedule, something had to give and that something was the visual design of the shows.

Cinematography in New Hollywood

The rise of a new group of American directors, influenced by European directors such as Truffaut, Godard, Fellini, Antonioni, and Bergman, began making films that defied the “traditional” old Hollywood. Then there was the coming-of-age of the Baby Boomers, who wanted movies that spoke to them. Finally, the end of the Hays Code in 1968 liberated directors from having to cater to the tastes of rural Midwesterners and southerners. Thus, out with Jane Wyman and in with Jane Fonda.

Cinematography also took an experimental turn. Of the Redford films I saw thus far, the cinematography and lighting choices by the directors were bold. In Butch Cassidy, directed by George Roy Hill (The Sting) with cinematography by Conrad Hall (Day of the Locust, American Beauty). The film opens with a scene in a saloon shot completely in a sepia tone with high contrast. The frames look like daguerreotypes from the nineteenth century, setting the period and mood for the action.

There is the bicycle scene, shot during the golden hour, that is vibrant and full of warm lighting. I cannot imagine a modern film using hair lighting as seen below on the character Etta Place, nor a director tolerating the clipped part on the left side of the frame. (And forget about the lens flare in a later scene. Old Hollywood would have considered that a mistake and reshot the scene.)

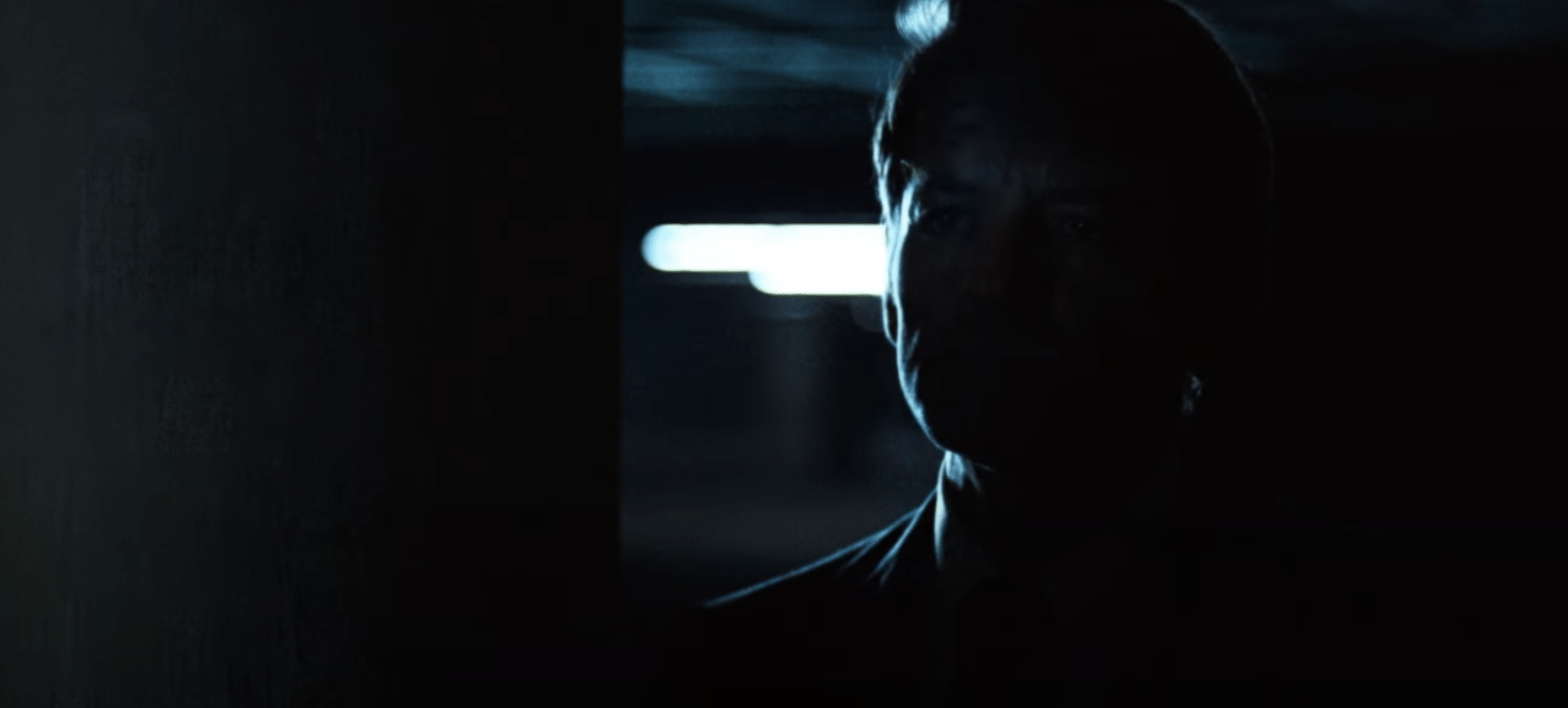

Same with All the President’s Men. Below is the scene where Bob Woodward (Robert Redford) meets with “Deep Throat” (Hal Holbrook) in the parking garage. This scene is pretty much completely clipped other than the right outline of Deep Throat’s face.

Note also the color grading in this scene. It is an eerie fluorescent blue. Consider the mood this scene sets for the viewer and now contrast it with the McDonald’s scene below.

In this scene, we have the fluorescent blue in the background, but then we have the warm gold tones with Woodward and Carl Bernstein (Dustin Hoffman) discussing the Watergate story.

The blue lights redirect your attention away from the counter to the characters of Woodward and Bernstein. But the blue lighting also adds a sense of depth to the frame. If this was shot today, my guess is they would do a close-up of Woodward and Bernstein to eliminate the distraction of the action taking place at the counter. But that would change the whole feel of the scene.

I would guess the lighting director used blue lights to illuminate the counter area, with a white lighting just off to the actors’ left to illuminate them. I wonder why the cinematographer, Gordon Willis (The Godfather, Annie Hall, Manhattan), did not simply use a lower T-stop to give a shallower depth of field? As you can see, the people in the background are in focus, which is puzzling, but not distracting because of the lighting choice.

Conclusion

Digital cinematography can produce some amazing output in the right hands. Check out The Brutalist if you do not believe me. But it requires directors and cinematographers to decide on a look for the film and then execute on it. I would also say that consideration of shooting for every viewing format (cinema, television, screen, smartphone) should be discarded. If you are making a movie to be watched in the cinema, shoot accordingly. If your intention is that the film should be seen on YouTube on a computer monitor, shoot accordingly. And, if you are making TikTok videos for smartphone audiences, shoot accordingly. In other words, the only consideration should be where you intend for your work to be seen and appreciated by audiences, be it the cinema, television, computer monitor, or smartphone screen.

It goes without saying we will never see another time culturally like the seventies. But I would like to see more atmosphere and character in filmmaking, along with unique and engaging stories like I am seeing in my self-guided Robert Redford retrospective. I am not holding out hope, though.

Bibliography

1976. All the President’s Men. Directed by Alan J. Pakula. Performed by Robert Redford and Dustin Hoffman.

1969. Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. Directed by George Hill Roy. Performed by Paul Newman and Robert Redford.

Leave a Reply